With the newly minted Minister of Foreign Affairs charting the raging sea of complex foreign policy, Indonesia's bid for OECD membership lurks behind. One of the challenges the Minister will have to answer is:

> What does it mean for Indonesia's health system development? While it is alluring to join the select club, the bid entails alignment with [OECD Health System Performance Assessment Framework](https://one.oecd.org/document/DELSA/HEA(2023)21/REV1/en/pdf) and a journey of iterative health system reform.

One overlooked item in the framework document is the unmet health needs, which were defined as **unmet needs for medical/dental examination due to financial, geographic, or waiting time reasons**. Indonesia does not have a comparable indicator. At best, Indonesia measures the other indicator, the population reporting unmet needs for medical care, which was surveyed with people being asked whether there was a time in the previous 12 months when they felt they needed medical care but did not receive it. However, Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Indonesia classifies it as unmet health needs.

Mind you, Indonesia is not alone in bidding for OECD membership. We have Thailand, a fellow Southeast Asia nation. From a health policy perspective, one striking difference between Indonesia and Thailand is the UHC Service Coverage Index (UHC SCI) achievement. Thailand scored 80, the highest in Southeast Asia, while Indonesia scored 55, just a sliver above Bangladesh (52), and Timor Leste (52).

Despite making strides in healthcare access, the Government of Indonesia often sees health through a narrow political economy lens, rather than a means to develop its human resources as an end. Arguing the ‘_unique_' challenges of Indonesia's geography and decentralization will not lead us anywhere.

The latest publication by the WHO Center for Health Development confirmed that currently, [there is no agreed standard measure of unmet health needs](https://wkc.who.int/resources/news/item/20-09-2024-spotlight-on-unmet-care-needs-among-older-people). Self-report surveys, such as by Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia (BPS Indonesia), asked a direct question about whether people perceived that there was a time when they needed health care and did not receive it. However, these direct measures do not provide further differentiation of the reasons given for why health care could not be obtained, or how coverage could be improved.

The way BPS's survey constricts the definition into a single-purpose question constrains the supposedly rich-in-meaning to understanding barriers to accessing healthcare. By OECD's standard, the assessment does not only consist of health-seeking behavior, but also personal factors, enabling factors such as financial and social support, and contextual factors such as geographical setting.

Who, or what, is the appropriate entry point, that we can pin down to initiate change and spur meaningful change? I’d pick **Universal Health Coverage**.

## Universal Health Coverage — cover what?

The concept of UHC was first introduced in The World Health Report: Primary Health Care (Now More Than Ever) in 2008 and later endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly on Global Health and Foreign Policy, urging countries to accelerate progress toward universal health coverage (UHC).

UHC is basically and simply a practical expression of the concern for health equity and the right to health for everyone. The idea is to enable equitable access to healthcare, protect every person from financial hardship in accessing health, and avoid impoverishment due to health shock.

There are fights over norms and international community responsibilities to materialize UHC, not to misguide and legitimate excessive health spending without clear public system strengthening. On [Textbook of Global Health](https://global.oup.com/academic/product/textbook-of-global-health-9780199392285?cc=us&lang=en&) (2017) even extended their concern that without health system strengthening, the agenda of UHC may benefit private interest alone and reinforce health care system inequity. I argue that Indonesia must start rethinking the UHC definition, before improving what it currently has and face the unintended consequences of exacerbating inequity.

> Getting the right definition is paramount to dictate policy development of health system improvement.

UHC is measured by the Universal Health Coverage Service Coverage Index (UHC SCI), which measures access to essential health services across populations. [Indonesia's progress in SCI relatively stagnated](https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/uhc-index-of-service-coverage) as the data above shows. UHC SCI breaks down the index into four domains and 14 indicators, measuring service coverage.

_Sub-indices and tracer indicators for UHC SCI Index of Indonesia. Source: 2023 Universal Health Coverage global monitoring report_

It is questionable that with [5,18% national unmet health needs](https://www.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/2/MTQwMiMy/unmet-need-pelayanan-kesehatan-menurut-provinsi.html), with even more bizarre provincial numbers, e.g., Papua Pegunungan has lower unmet health needs than Bali, **Indonesia only scores 55 in UHC SCI**.

What happened? From my perspective, it is the lack of consideration for the journey between health needs to health-seeking behavior to health service utilization, and consequences of those services.

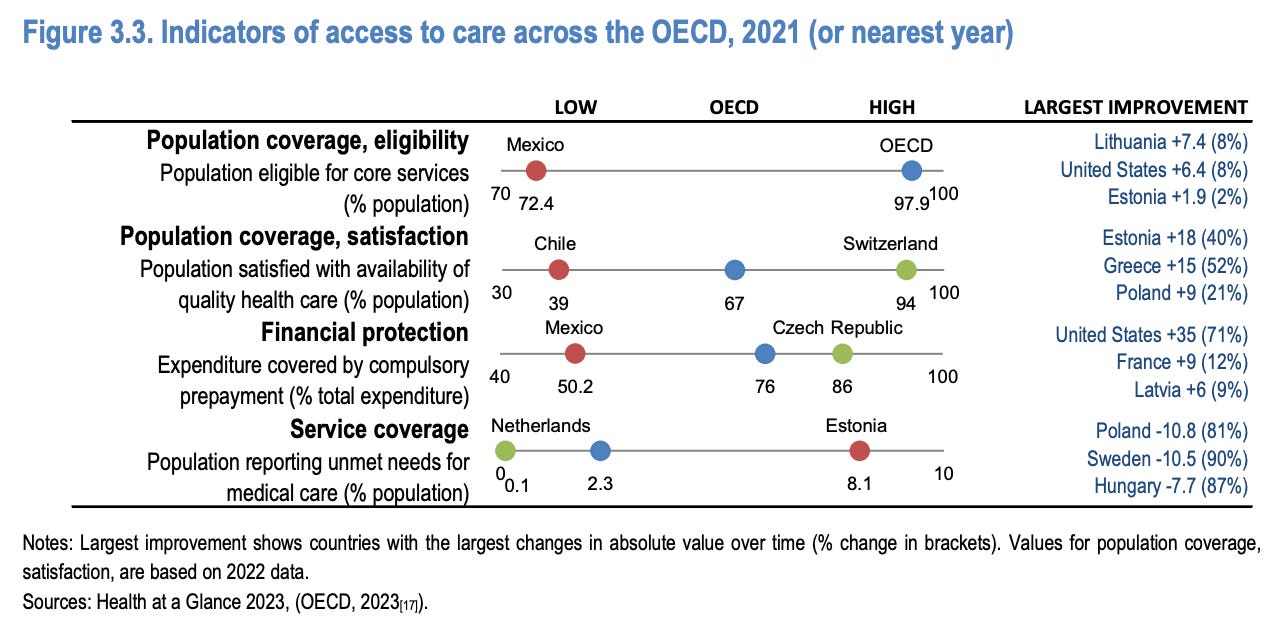

> Indonesia must reimagine, at least align with OECD countries in integrating the demand side of healthcare services, such as affordability, waiting times, and satisfaction with the quality of healthcare services.

*Source: OECD Health System Performance Assessment Framework 2023*

Capturing these demands side will convert the enormous-yet-untapped health needs in Indonesia, and ensure equitable health access is realized.

## So what now? Unsolicited advice for policymakers

**First**, broaden the definition of unmet health needs. Incorporate demand-side metrics to not only cover the supply side of healthcare and infrastructure. An early understanding of gaps happening in every postal code of Indonesia will enrich understanding and guide policymaking.

**Second**, invest and streamline data collection. The self-report survey has its limitations. The government must continue to invest in digitalization, not only in the health sector but the ecosystem that feeds data into the health sector. Streamlined data collection will also enable Indonesia to make precise, data-informed decision-making, from national- to family-level interventions.

**Third**, policy innovation that prioritizes healthcare accessibility, affordability, and availability. The government of Indonesia should leverage the huge untapped market and deploy several policy prescriptions to improve access to health, such as strategic prioritization of pharmaceutical products to be locally manufactured, expedited access to innovative products, pressure subnational governments to address health problems, and mobilizing domestic resources.

## Conclusion

Aligning with OECD definitions not only will put Indonesia on par with OECD countries in their public service quality and human resource development but also ensure Indonesia is moving in the right direction by first, contesting the norm and defining the right indicators to measure performance. The last thing Indonesia wants to do in its long-term planning, including its bids for OECD membership, is being misguided by its data and not knowing where it goes wrong. Or worse, making it to the rich countries club, but the majority of Indonesian people’s livelihood is buried under the half-true definition.